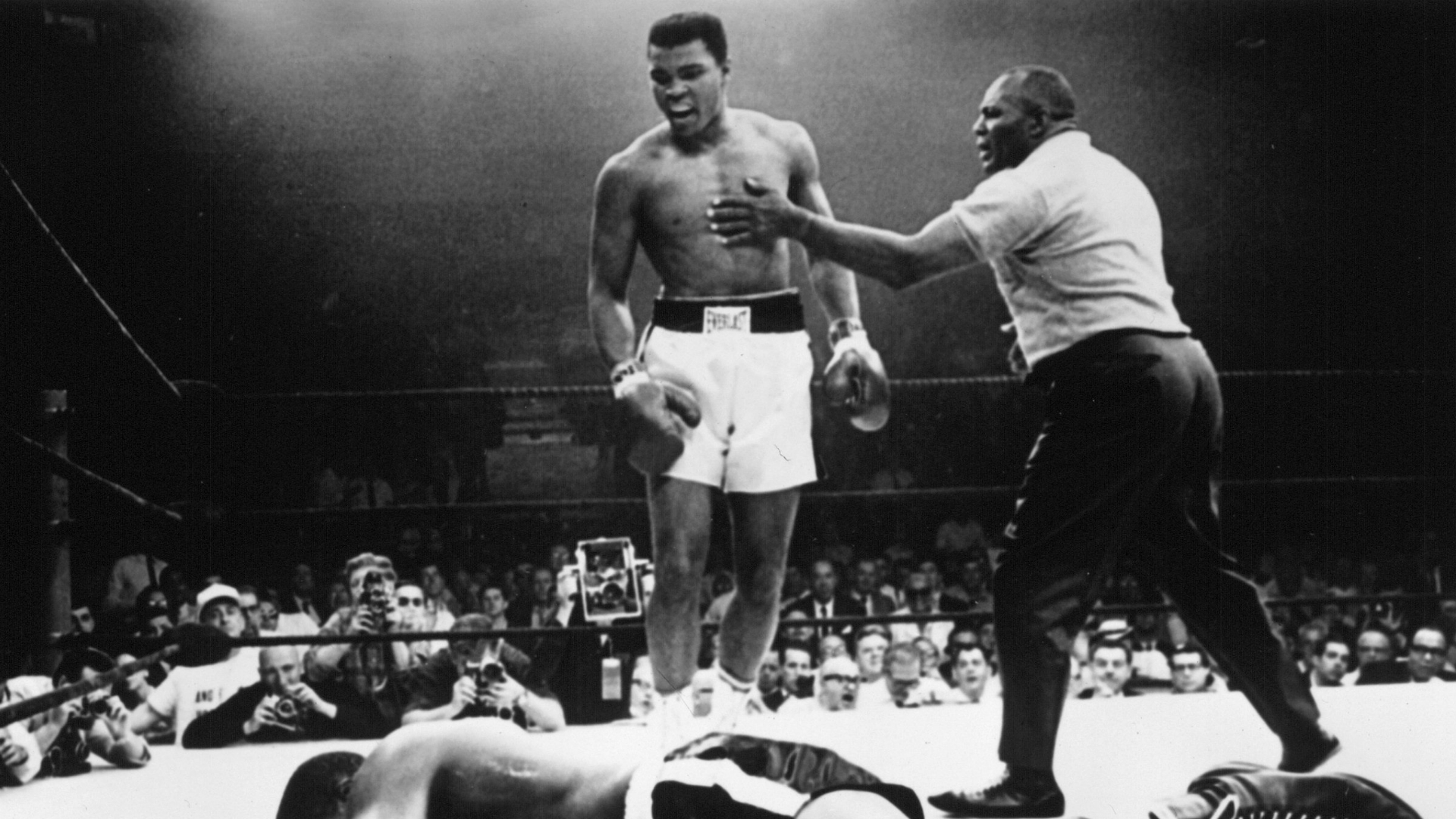

“He was the greatest of all time, and it has zero to do with what he did inside the ring.”

LeBron James

ON FRIDAY, JUNE 3RD, Muhammad Ali died at age 74.

This statement means different things to different people. For my 23 year old self, Ali’s reign as The Greatest was long before my time, and boxing was never a relevant sport to me until 2015, when the underwhelming Floyd Mayweather vs. Manny Pacquiao fight and hype thereof dominated news outlets. (I still don’t follow boxing, really.)

But unless you’ve been lucky enough to be entirely insulated from the 24-hour news cycle, you can see that Ali’s death meant so much to so many;[ref]Even if nobody gives a shit anymore because of the Stanford rape case.[/ref] his ripples were so pervasive that online life Saturday seemed divided into two categories: Muhammad Ali and everything else.

I’ll spare the writeup on his death, many others have done it quite well. What I am more interested in (and where I can more credibly contribute to the conversation) is the conversation I had with myself reading about Ali; rather, the nature of sports heroes and the overall sports experience in culture.

I’ve spent an embarrassing amount of shower daydreaming thinking on why the athlete’s experience is so much more communicable to Joe Schmo than the musician’s experience with which I’ve devoted 16 years and counting. Seriously, the journey of the athlete and the classical musician are eerily similar:

- Both start training at an impossibly young age

- There is a strong correlation with parent success in that field[ref]Steph Curry and Klay Thompson of the soon-to-be-champion Warriors both had NBA players as fathers. And of course, we all know that prodigial talent that has a whole lineage of musical excellence.[/ref] and success of their children in that field

- A large amount of children play on an amateur level; it’s mostly just a means of directing youthful energy through a positive outlet and “keeping the kid out of trouble”

- As children get older, through middle school, high school, and college, the stakes rise, the scene becomes more competitive, and the less talented are weeded out

- Eventually, the best of the best are paid to do, at an elite level, what they’ve essentially done and trained for their whole lives, and the public pays money to watch them.

And yet somewhere along the way, the two paths diverge sharply. College football and basketball is a multi-billion dollar industry,[ref]The NCAA signed college basketball’s March Madness over to CBS for 14 years with a $10.8 Billion dollar contract[/ref] while university orchestras and wind ensembles get less airtime than college lacrosse, college bowling, and Steph Curry’s two year old daughter. The NFL has the most viewed event on television year after year, whereas one of classical music’s most famous conductors had to fight for a two second spot on its halftime show.[ref]I wrote about Dudamel’s Super Bowl 50 appearance here.[/ref] If you want to talk pocketbooks, a 19 year old NBA rookie drafted in the middle of the first round is guaranteed a little over $3,000,000 on signing, whereas we throw parties for our colleagues that land a principal orchestra spot making $45,000 a year.

How did this happen? Why is public perception of sports enough to merit a $62.8 million dollar football stadium for high schoolers, but mass hemorrhaging of arts funding for those same high school students?

Rendering of the upcoming high school stadium in Texas. Hard to think of a better way to spend $62.8 million dollars!

BEYOND THE GAME

I’VE CONSUMED a pretty unhealthy dosage of sports media over the past five to six years of my life. This is for a variety of reasons: insecurity about my ability to relate to other men, an upbringing by a family of shocking sports enthusiasm, and the fact that watching a 6’9″ human dunk a basketball after running over 20 miles an hour is fucking exhilarating.

It was only recently that I realized that none of the above has anything to do with the actual games of football and basketball.

Ultimately, while the games provide entertainment, sometimes of the incredibly riveting variety, the joy of consuming the NFL and NBA comes not from the sports themselves, but from the athletes and the narratives their exploits weave. Steph Curry doesn’t just shoot a record number of 3-pointers, he’s “changing the game of basketball” and “bending the court to his will.” Tropes like these can be forced at times in sportswriting, but they have been sneaky effective at contextualizing athletic achievement in ways that a casual fan can discuss.

The equivalent simply does not exist in classical music. We don’t have lofty platitudes when an established musician wins a competition, or sells a record album. We don’t talk about Lang Lang “dominating the league” or debate whether Yo-Yo Ma will be a Pro Bowler this year.[ref]He’ll make it for sure this year.[/ref] These conversations come sparsely, and often only to recount a dead musician’s career in retrospect.

Yo Yo Ma with another clutch performance in the 4th quarter.

Some reasons for this, of course, are obvious: music is a subjective field with no scoreboard, and there are no obvious ways to compare different musicians, even those who play the same instrument. For instance, we can very easily compare lifetime statistics in basketball and note that Magic Johnson made shots at a greater percentage in his career than Kobe Bryant. But we can’t, nor should we, have advanced metrics on how many missed notes players have a season or shifts they miss.

So why haven’t we made the story of the artist as relatable as that of the athlete?

My theory is that great sports heroes are lionized not solely for their achievements on the court, but for their worthiness as an ambassador for the most transcendent human qualities: saving peak performance for when the stakes are highest and the lights are brightest (Michael Jordan, Joe Montana),[ref]A combined 10-0 in championship games.[/ref] achieving wild success when superiors peg you to be mediocre (Steph Curry, Tom Brady),[ref]Steph, the NBA’s first unanimously voted MVP, was drafted behind seven other players. Brady, the NFL’s first unanimously voted MVP, was drafted behind 198 other players in the sixth round.[/ref] prevailing over the Goliath as a David (Miracle on Ice hockey team), or simply stretching the limits of what humanity ever thought possible (LeBron, Michael Phelps).

Society can relate to these feelings in one way or another—nailing a high-stakes audition or interview, succeeding despite a revered authority figure that told us we’d never amount to anything. We’ve all been underdogs; we’ve all marveled at Stephen Hawking and Elon Musk as much as Tiger Woods and Lionel Messi.

But the classical experience, despite the same hours grinding at our craft, toils thanklessly, while our athlete counterparts enjoy otherworldly fame and glory. Our high-stakes auditions are dissected by a panel of less than a dozen behind a curtain, not by major television networks on “Draft Day” and thousands of internet blogs and Facebook comment threads.

This is literally a three day special. For one sport.

Somehow, the rawness of the artist’s journey is lost. Dramatized movies about that experience may win Oscars, but they feel like distant caricatures—a portrayal of an otherworldly journey foreign to the “actual” human experience. The classical artist just doesn’t have that common man’s catharsis that sports movies provide: think Remember the Titans, Rocky, Hoosiers.

Maybe it has something to do with the language with which sports are discussed. “It’s just their year. Defense wins championships. Can’t argue with rings. Man, he just finds a way to win. What a clutch gene. The game was a blowout. Steph willed them to a win.”

We describe players with one liners. “Dominant. Killers. Assassins.” Repetitive? Sure. But effective, and oddly satisfying.

During my time at Juilliard, I relished being able to talk shop with the few basketball fans that there were, because it was so easy to feel like you could drop into a conversation about sports and instantly speak the same language. No such vernacular exists to discuss the concert experience. Music critics, the few that are left, describe in nebulous language like “exquisite”, “riveting”, or in my case, “aplomb.”

It makes me wonder—does the very nature of the classical experience lend itself to an insurmountable foreignness? Or have we made it foreign, pulling ourselves away with a lack of urgency towards societal integration and dashes of that special elitism we all know and love?

Muhammad Ali was The Greatest. The numerous pieces I’ve read about his legacy, complicated though it may be, confirm that assertion. No athlete has had a more profound effect on both his sport and society as a whole. But his accomplishments in the ring were merely a footnote to his life and legacy outside the ring. I’m convinced that classical music as a field has yet to figure out that second part of the equation: the connection of great art to human greatness.

I also realize that this isn’t inherently bad. The financial compensation of professional athletes comes with a large cost: an insufferable amount of scrutiny and unwanted fame. For the most part, you can dine where you want if you’re Hilary Hahn or Joshua Bell and you won’t be mobbed by fans. Conversely, even relatively anonymous rookie Jahlil Okafor of the Philadelphia 76ers was heckled endlessly going out to a club in Boston. Tony Romo has one bad game and his job performance is a trending topic on Facebook, and suddenly hundreds of thousands of people think you should be fired (or worse). Hell, Michael Jordan cries once and he’s an internet meme synonymous with failure for eternity.

RT @bdotTM: (Insert michael jordan crying here) pic.twitter.com/X0iT5AgKKm

— Byron Young (@ByronYoung24) January 14, 2016

So maybe we don’t want classical music in the national conversation to the degree of sports; perhaps it comes with more baggage than we can handle. Music might also have different limitations: art might just be too subjective to inspire the kind of controversy (and resulting conversation) that a bad referee call or singular missed shot does.

But with the arts clawing for every bit of relevance in today’s landscape, I think it’s something worth thinking about.

Thanks for reading. If you have thoughts, I’d love to hear them in the comment section below. Contact me anytime with this link. If you like my content, please share it on Facebook with your friends and enemies.

Recent Comments